In the run up to International Women’s Day, Art on a Postcard is fostering a conversation about the stories women’s bodies tell in life and art. With the release of a limited edition Skinscape print by acclaimed British artist Caroline Coon, we explore what it takes to represent the body as a landscape. What affinities do the valleys and furrows of our skin have in common with nature? And why do we look for ourselves in nature?

In this blog post we explore the history of female explorations of the body, specifically those which view the self as part of a landscape. Through the work of Ana Mendieta, Laura Aguilar, and Helen Chadwick, the body is rendered as part of a landscape which challenges, archives, reflects, and evolves in relation to our personal and collective memory.

Historical depictions of Mother Earth

Women artists have historically found courage in the representation of their body through or within nature. In the mid-twentieth century this could be seen as an act of reclaiming the connection which had been inscribed onto women and nature for centuries. These ideas are illustrated quite explicitly in American history, in which the prairie or frontier were imagined as virgin bride or welcoming benevolent mother. John Gast’s American Progress, 1873, depicts the classical goddess-like female form of ‘progress’ gracing the colonial expansion westward. Similarly, Alexandre Hogue’s Erosion No. 2 – Mother Earth Laid Bare, 1936, transposes a female body into the landscape. The figure in the drought-stricken farmland is a personification of a deformed earth at the expense of over-farming. Hogue, despite attempting to expose the disillusioned imaginary of progress in harmony with nature, continues to rely on this stereotype.

Ana Mendieta

"The obsessive act of reasserting my ties with the earth is an objectification of my existence."[1]

– Ana Mendieta

Ana Mendieta (1948-1985) was born in Cuba in 1948 and was exiled from her country at the age of twelve. Her sense of loss and dislocation from her native landscape became a source of inspiration for her work. Started in 1973, Mendieta presented one of the most iconic explorations of women’s bodies and land art in the photographic Silueta series. The Siluetas are repetitive, obsessive, photographs of the imprint of her own – or a collective ‘Everywoman’s’ – form on and in the earth. From flowers to gunpowder, open graves to eroded riverbanks, Mendieta’s seminal works reopen the dialogue between femininity and nature.

For the early pieces, the artist uses her own body as a silhouette, as seen in Silueta, Imágen de Yágul, 1973. Hundreds of flower stems grow seemingly through her body as she lies in a Zapotec tomb, merging the symbolism of fertility and death. However, Mendieta eventually removes her body completely from the compositions, leaving only impressions, as seen in Silueta, Untitled, 1976.

Left: Ana Mendieta, Silueta, Imágen de Yágul, 1973.

Right: Ana Mendieta, Silueta, Untitled, 1976.

The photographs not only create a topology of abstracted feminine forms, but their setting also situates the body within the archetype of Mother Earth. For the latter, Mendieta’s series has been criticised for ‘embracing a conventional alignment of the female body of nature, thereby presenting an ahistorical, essentialist conception of a woman.’[2] But historians have also stressed the nuances in the series which offer alternative readings of the work. Susan Best continues to argue that Mendieta uses the trope in order to subvert and reclaim the predominantly masculine historical canon within art. Instead, her Siluetas emphasise the reciprocity between body and land.

This brief body of work from Ana Mendieta’s practice sets the scene for modern and contemporary engagements between landscape and female bodies. Body and nature are impressed equally into one another, being both itself and the other.

Laura Aguilar

Photographer Laura Aguilar (1959-2018) was born in San Gabriela, California, and had herself embodied numerous identities throughout her life; artist, woman, Chicanx/Latinx, queer, and lesbian. Her work confronts and makes visible the ways we see ourselves and the ways others see us, melding inward and outward impressions.

Around ten years after the publication of the highly influential essay by Deborah Bright titled “Of Mother Nature and Marlboro Men,” Aguilar’s practice shifts to the connection between body and land. First in 1996, then 2006, Aguilar creates a series of self-portrait photographs depicting her naked body in the arid Joshua Tree desert. The later series, titled the Grounded Series, imagines the topography of the artist’s own body in relation to the rocks and boulders which scatter the landscape. The setting of her photographs in the desert, a site of inhospitality, and her own identity as a Mexican American illustrates the inextricability of human reference and the land.

Unlike Mendieta, Aguilar’s body does not act as either a benevolent mother or sublime virgin goddess. Rather, her body inhabits the scene with no attempt to stand out. She simply blends in, existing in the landscape. Aguilar’s photographs are made without the explicit privileges of earlier feminist body-based works, she was not white nor heterosexual nor a woman who believed her body as conventionally desirable. In the photographs where her back faces the viewer, such as Grounded 111, 2006-2007, her curled form sits in direct alignment with a large monolithic rock. Her sense of self is no longer isolated within a discrete female form, rather her body becomes a landscape for her to enact her identity upon.

Left: Laura Aguilar, Nature Self-Portrait 14, 1996.

Right: Laura Aguilar, Grounded 111, 2006-2007.

Helen Chadwick

Helen Chadwick (1953-1996) was born in 1953 in Croydon, London. In her early career Chadwick experimented using her own body in performance works, such as In the Kitchen, 1977, her MA graduation project, which challenged the reinforcement of gender roles. Her work continued throughout her career to merge ‘theoretical ideas and fleshy physicality.’[3]

In 1988, Chadwick won a residency on the Pembrokeshire coast to further investigate a burgeoning interest in cells – viruses in particular – which resulted in a series of Viral Landscapes. In these pieces Chadwick drew connections between the nature of viruses being unable to exist without a host, such as our bodies with the natural landscape.

The photographs of the coastal landscape are combined with paintings the artist created on its shorelines as well as images of Chadwick’s own cellular tissue. Enlarged under a microscope, Chadwick used photographs of tissue removed from her own body such as her mouth, ear, blood, cervix, and kidney, and ascribed the different biological forms to different parts of the sea or cliffs. The works were made at the height of AIDs awareness in the late 1980s and present the differences and similarities between our bodies and nature.

Helen Chawick, Viral Landscapes, 1988-89.

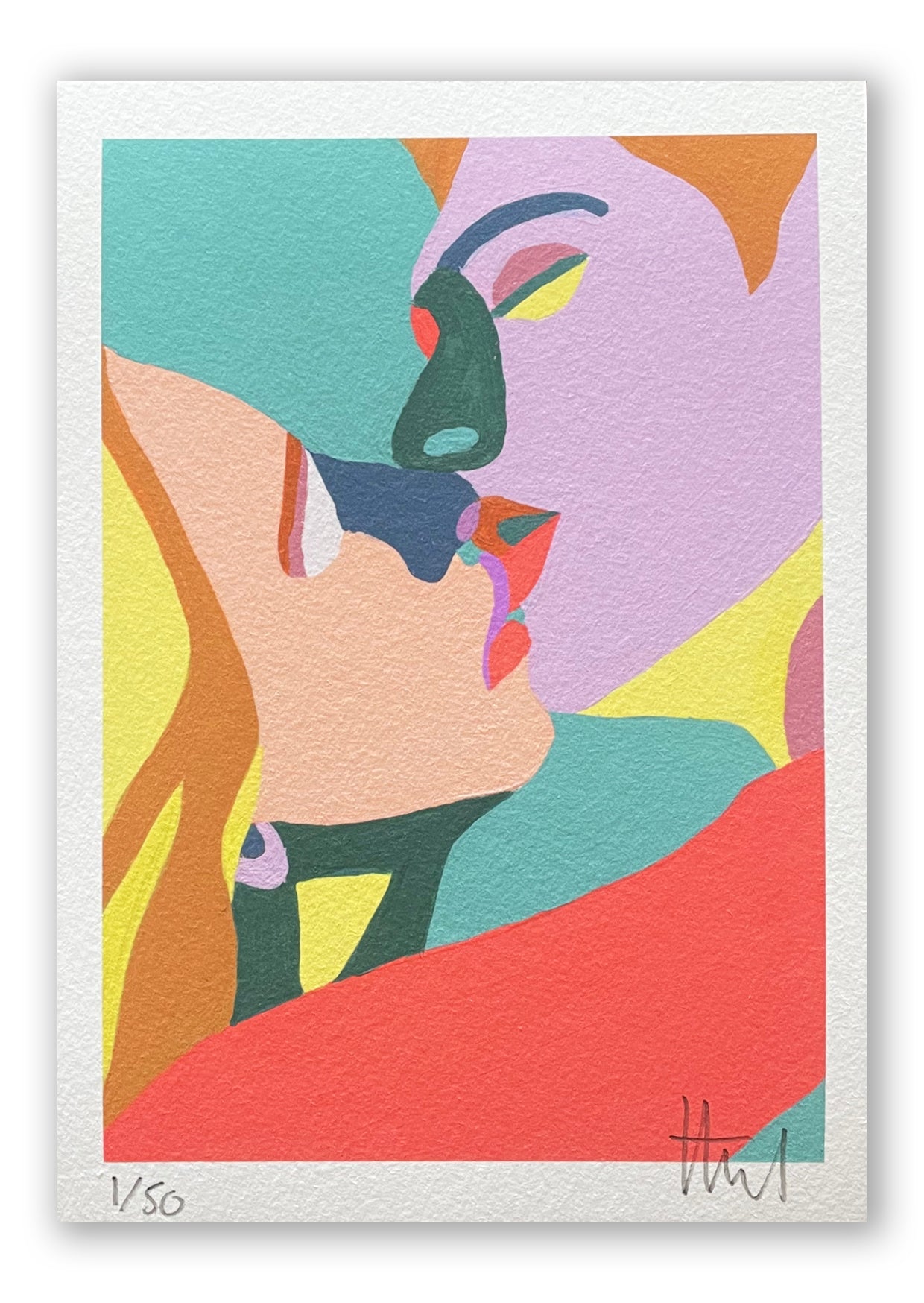

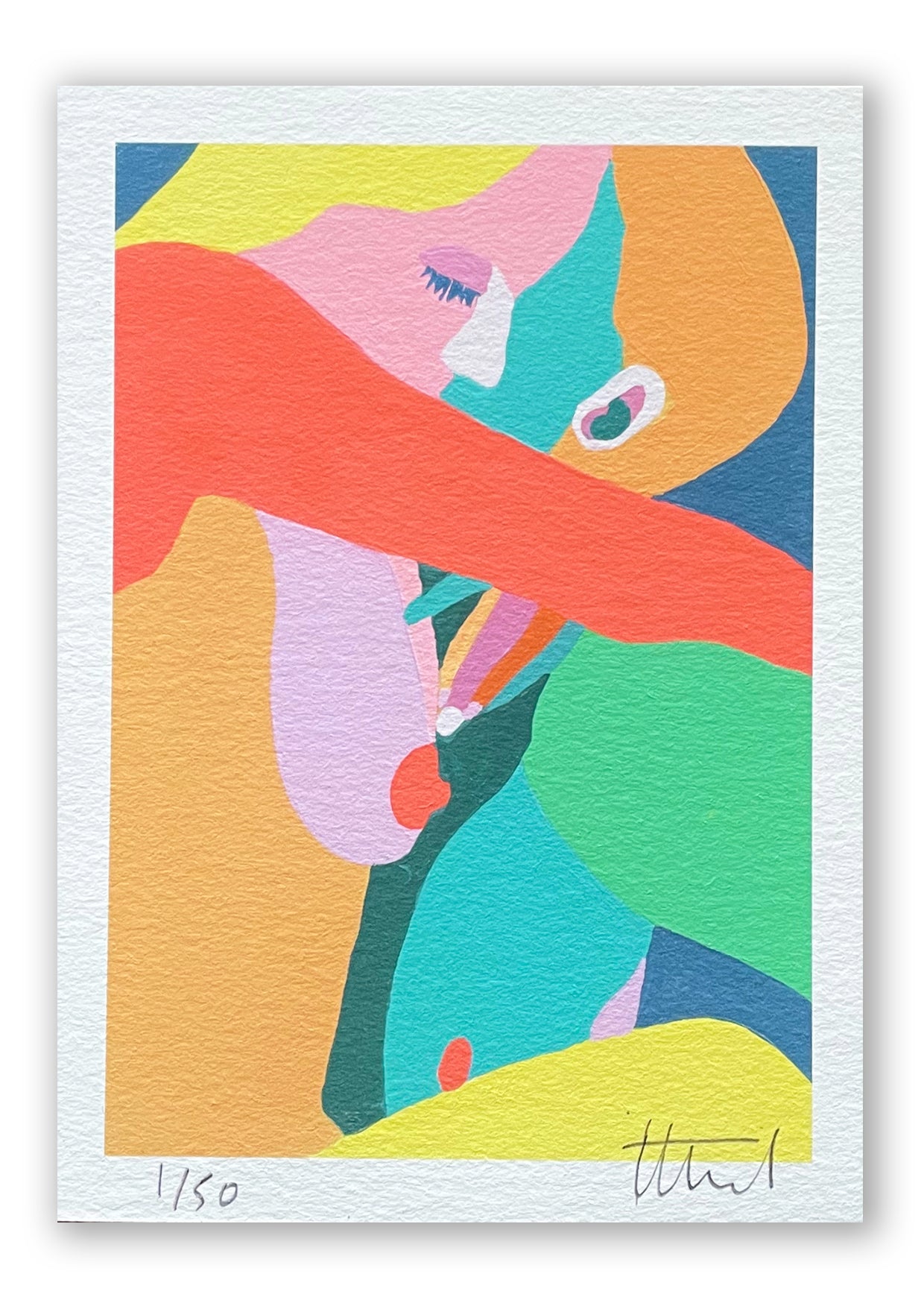

Caroline Coon

To return to an artist represented in our upcoming International Women’s Day Auction, Caroline Coon’s work for Art on a Postcard now and in the past, has similarly explored the body as landscape. As with Mendieta’s topology of abstracted feminine forms, Coon’s Skinscapes reflect landscape through an abstraction of the self. The full-frame composition separates the body from its context, yet we understand enough to grasp that a ‘whole’ is formed from these parts. This decontextualisation encourages us to see the body in the way that we see a landscape, a unique interconnected system.

Furthermore, Coon’s unapologetic depictions of overlooked groups of female bodies, such as drug-users and sex-workers, maintains that bodies are imperfect. The experiences which mould and mar our skin are unique to us, the experiences we have lived through and therefore should be cherished, celebrated. These scars and stretch marks are as natural as the formation of great mountain ranges or rivers. We can argue that Coon’s investigations offer a way to bridge the ethereality of femininity with the ‘ugliness’ of life by viewing our skin as an archive.

Notes

[1]Mendieta, Ana. “A Selection of Statements and Notes.” A Tribute to Ana Mendieta. By Linda Montano. Sulfur 22 (1988): 70-74.

[2]Best, Susan. "The serial spaces of Ana Mendieta." Art History 30, no. 1 (2007): 57.

[3]Art UK: https://artuk.org/discover/stories/helen-chadwick-body-artist-and-feminist-vanguard

Written by Victoria Lucas