John Milton’s epic poem Paradise Lost, describing the Christian story of Adam and Even in the Garden of Eden, and the ensuing fall of man, is considered one of the greatest pieces of literature in the English language. Since its publication 358 years ago Paradise Lost has become a ‘fable’ of choice. Its legacy is ingrained with dilemmas of choice and uncertainty which seem to perpetually speak to twenty-first century challenges: gender, race, class, and political polarisation. Paradise Lost gave aesthetic form to problems that Milton addressed in his earlier works and continues to give shape to these problems in whatever time period it is re-editioned.

There are 277 editions of varying notes and forewords of Paradise Lost held in the British Library’s online catalogue.[1] The Cosmos of Paradise Lost, The Metaphoric Structure of Paradise Lost, The Astronomy of Paradise Lost, The Moral Paradox of Paradise Lost, The Construction of Paradise Lost; the innumerable studies of Milton’s work are testament to its importance in the cannon of English literature and theology. My interest, however, is to uncover the cannon of Paradise Lost imagery within the contemporary art. How has Milton’s work, as its theological currents have ebbed, become a point of departure for artists interested in political revolution and freedom?

Paradise Lost: Then

The most well-known illustrations of Paradise Lost were created by Gustave Dore. While Milton’s poem featured Adam and Eve as principal characters, Dore’s Paradise Lost illustrations are dominated by scenes of the angelic and demonic. The dramatic, high-contrast engravings have defined the work for many of its readers, further distancing itself from biblical symbolisms. For example, the plate depicting Satan's journey through hell after being cast from heaven simultaneously captures the grandeur and torment of Milton’s narrative.

With head, hands, wings, or feet, pursues his way, / And swims, or sinks, or wades, or creeps, or flies. Engraved by Adolphe Gusmand. (Left)

Inside cover of Paradise Lost featuring illustrations by Gustave Dore. (Right)

Paradise Lost: Now

“Everybody talks about Paradise Lost and nobody reads it.” – Unknown, late nineteenth-century.[2]

A recent publication by Orlando Reade titled What in Me is Dark? The Revolutionary Afterlife of Paradise Lost delves into the ways that Milton’s Epic has been read across centuries and continents to influence some of the most influential political figures and writers. From Malcom X to Virginia Woolf, Hannah Arendt to Thomas Jefferson, Reade uncovers how Milton’s own plot recalls England’s Civil War in the 1640s and has since incited a legacy of revolutionary thought. When reading the book, I attempted to find examples of visual artists similarly inspired by Milton's work. Although few, I was able to find examples of contemporary artists who have truly engaged with the work and applied it to their present moment. These modern interpretations demonstrate how Milton’s narrative continues to inspire not just literature but art.

Chris Ofili

Installation View of Chris Ofili, Paradise Lost, September 14—October 21, 2017, David Zwirner, New York

In 2017, British painter Chris Ofili opened a new installation at David Zwirner in New York. Explicitly labelled Paradise Lost, Ofili takes the latter of Milton’s title quite literally. A monumental metal chain-link fence prohibits viewers from fully seeing the exhibition’s four paintings and wrap-around mural. The result, a crude division of space which left visitors only a four-foot walkway to move around the gallery. Peering through the fence, into some sort of ‘inner sanctum’ or metaphorical Paradise, four black and white canvases remain out of reach of closer inspection. Similarly, constrained too closely to the surface of Ofili’s mural, the twenty-four dancing figures set amongst a prelapsarian Eden can never be comprehended as a whole. In Paradise Lost, Ofili’s cage excludes and contains. If our backs are turned to the mural, we ignore the Paradise closest to us in favour of longing for that out of reach place.

The press release quotes Paradise Lost’s Book XII, the moment when Adam and Eve taking leave of the Garden of Eden:

The world was all before them, where to choose

Their place of rest, and Providence their guide:

They hand in hand, with wandering steps and slow,

Through Eden took their solitary way."

The installation is a direct question toward freedom and choice. Expanding on a work from the same year at the National Gallery, London, Ofili poses "the question of the sweetness of the song—is the sweeter song the song of the uncaged bird, or the song of the caged bird? And what that really is asking about liberation and constraint, and how that could potentially relate to being human."[3]

An article from the Brooklyn Rail laments at the inclusion of reference to Milton, focusing too obviously on the theology of the work: “No, Chris, don't send us to Milton's epic seventeenth century saga predicated on man's disobedience to God.”[4] But if repeating Christian thought was all that this poem did, it would hardly have had such a deep influence among so many non-Christian readers and for so many years. So yes, Chris, please do send us Milton’s way.

Installation View of Chris Ofili, Paradise Lost, September 14—October 21, 2017, David Zwirner, New York

Ofili’s depicted expulsion from paradise is neither violent, nor filled with despair.[5] Rather, this loss is mindful, self-aware, and accepting of the responsibilities of our actions. In this way Ofili reiterates one of the unavoidable points within Milton’s saga: the false dichotomy between good and evil. Throughout Paradise Lost the figure of Satan reminds us of the nuances between binary oppositions, urges its readers: sympathise with me.[6] Ofili’s work reflects this system where the binaries of loss and return/gain/recovery flow into one another.

John Akomfrah

Immune to the wonder that others praised Milton’s Paradise Lost, the philosopher Edmund Burke held steadfast in his opinion that the poem is “dark, uncertain, confused, terrible, and sublime to the last degree.”[7] This sublime aesthetic that Burke mentions was caused by encounters with things that are vast, terrifying, and unknowable. Edmund Burke places terror as the ruling principle of the sublime, the strongest emotion which the mind is capable of feeling.[8] Paradise Lost exists as a Sublime work of literature because of the awe-inspiring nature of the divine which Milton evokes.

Still from The Nine Muses, John Akomfrah, 2010

Ghanaian British artist John Akomfrah’s film The Nine Muses embodies this feeling in its vast shots of distant snow-covered mountains juxtaposed with archival footage. The film, released in 2012, presents a full-length meditation on migration, feelings of uprootedness, displacement, and a loss of innocence. Throughout The Nine Muses a multitude of voices read from text’s such as Milton’s Paradise Lost, Homer’s Odyssey, and Beckett’s The Unnameable. Akomfrah speaks to this seemingly juxtaposing combination:

It looks eclectic but actually there's something that connects the motives of Paradise Lost with Beckett's Unnameable because both are obsessed with this question of becoming. Paradise Lost is about how the Fall came in, which by implication is about how 'man became man'."

His film represents the becoming of migratory bodies, archival material of workers arriving from the Caribbean, men in factories pouring molten metal, is spliced with a lone figure approaching the frozen coastline. Britain is shown as a cold, inhospitable place, overlaid with the voice telling of ‘man’s first disobedience’ the migrant’s expulsion from paradise could not be any more apparent. This world is a distinctly postlapsarian Eden.

Amy Hui Li

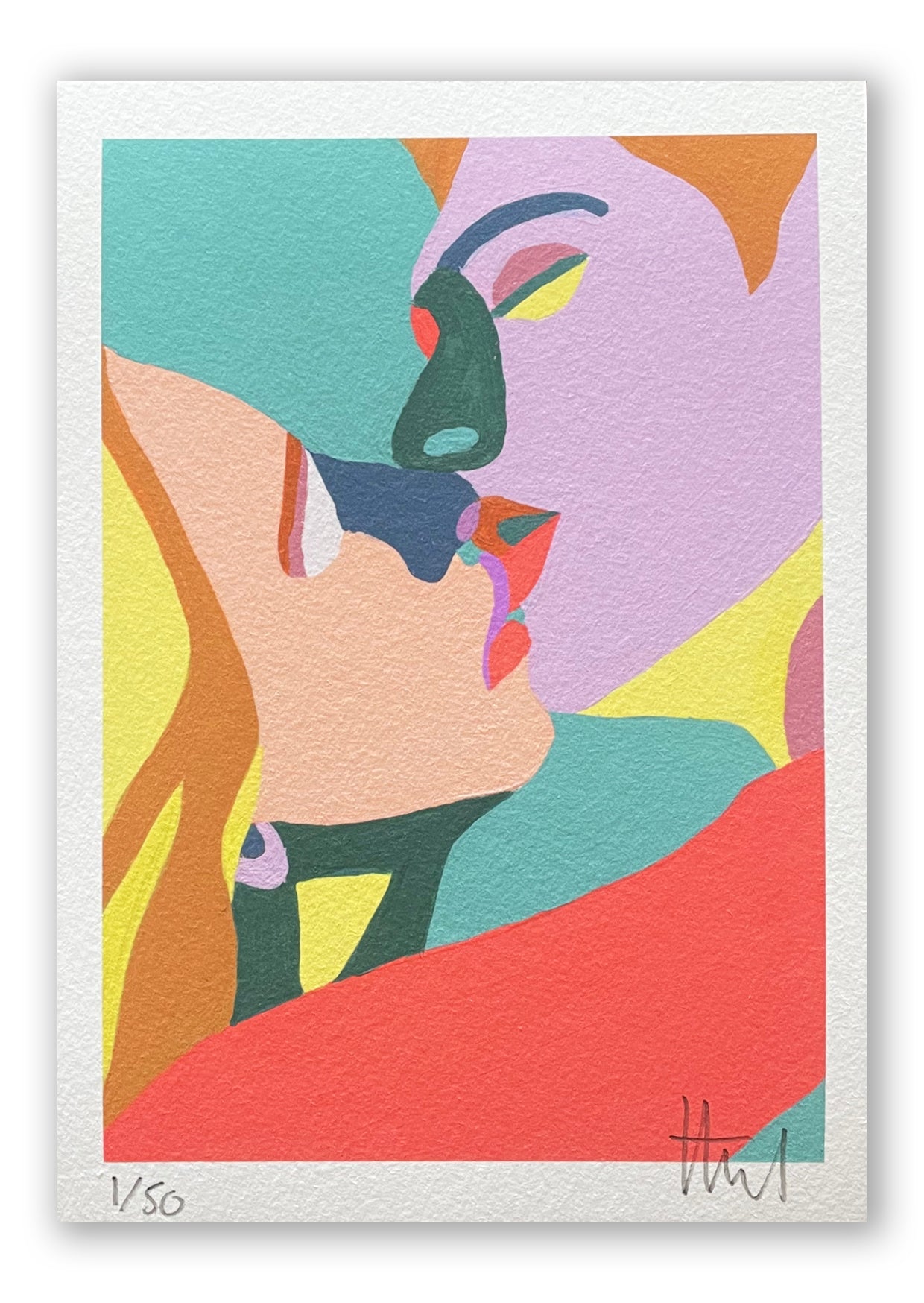

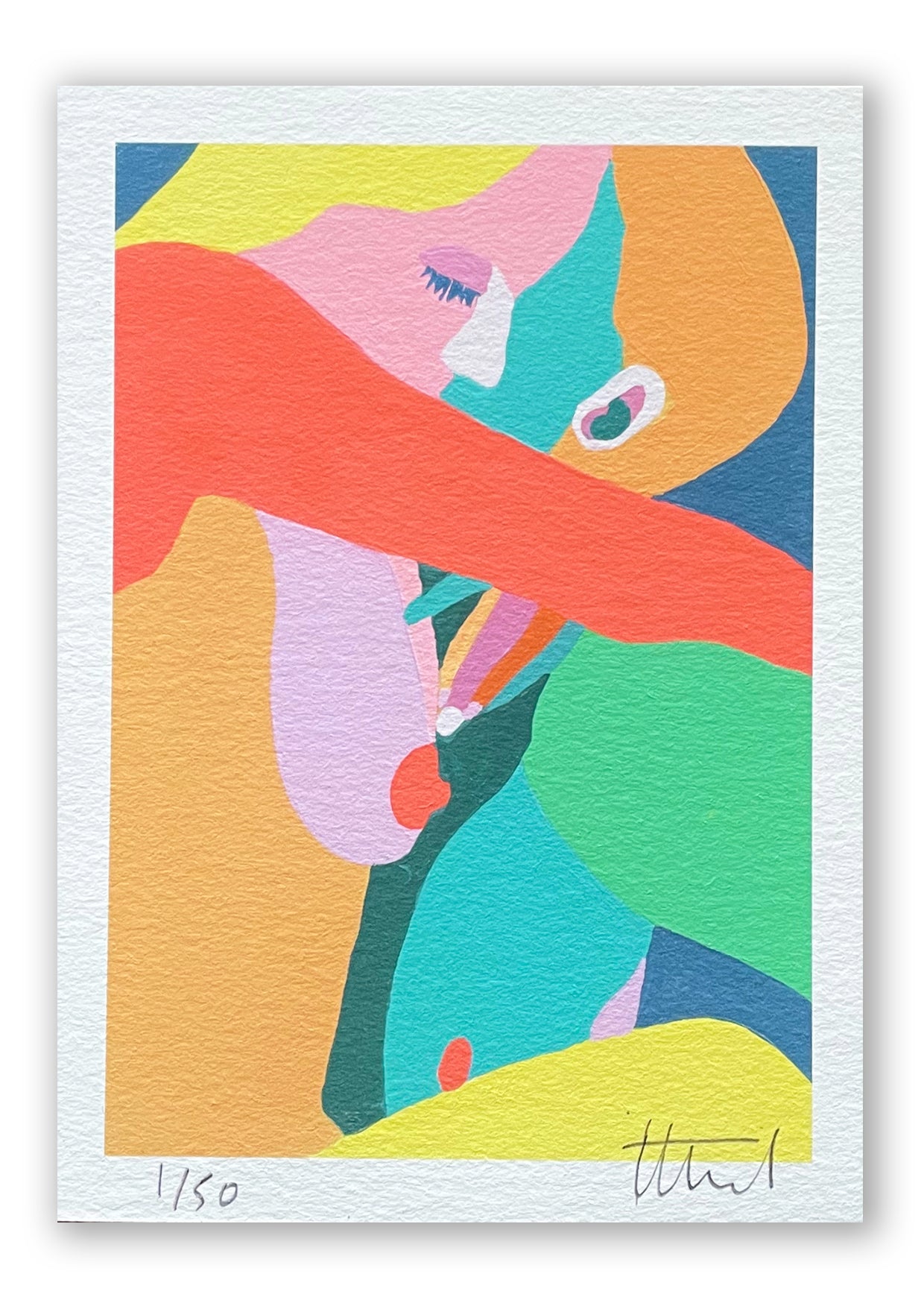

Installation View of paradise lost Solo Exhibition, 12th Dec 2024 - 19th Jan 2025, Unit, London.

In an example taken from this year, Amy Hui Li's first solo exhibition with Unit takes Milton's Epic as its namesake. It is not clear if Li was directly influenced by Paradise Lost when creating these specific sculptures. However, the nature in which the churning organza canvases haunt the space undoubtedly speaks to the sublime grandeur and terror in the text.

The exhibition texts issues that Li's works 'reconsider the ideas of sin and grace in a contemporary context.'[9] Li also draws from the song Paradise Lost/失乐园 written by Wyman Wong and performed by the band Grasshopper, which reflects the contradictions of a harsh yet fascinating world. Similarly to Chris Ofili and John Akomfrah, her paintings explore personal struggles and healing, revealing her own unique interpretation of Milton's poem.

Notes

1. Consult the British Library Catalogue here.

2. Reade, Orlando. What in Me is Dark? The Revolutionary Afterlife of Paradise Lost. London: Jonathan Cape, 2025.

3. Chris Ofili in imagine …, "Chris Ofili - The Caged Bird’s Song," BBC One, Winter 2017.

4. Read the Brooklyn Rail article: https://brooklynrail.org/2017/11/artseen/Chris-OfiliParadise-Lost/

5. Read the Vulture article: https://www.vulture.com/2017/10/chris-ofili-still-fearless.html

6. Reade, Orlando. What in Me is Dark? The Revolutionary Afterlife of Paradise Lost. London: Jonathan Cape, 2025.

7. Ibid. (As above)

8. Burke, Edmund. “A Philosophical Inquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and the Beautiful,” [1757]. In: Art In Theory 1648-1805, edited by Adam Philips (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2012), 516-525.

9. Read the full exhibition text: https://unitlondon.com/exhibitions/amy-hui-li-paradise-lost/

Written by Victoria Lucas