Marcus Cope is a figurative painter whose subjects are often derived from his personal history, memories and current life. Cope’s childhood trauma coupled with his experience as a father has been a particular influence. Cope completed a Foundation in Art and Design at Bath College in 1998, a BA (Hons) in Fine Art at Coventry University from 1999 to 2002, a Postgraduate Diploma at Chelsea College of Art and Design in 2003–2004, and an MFA in Fine Art at Chelsea College of Art and Design in 2006. Solo exhibitions include Another Think Coming at Artuner, London (2025), Silver Linings at PEER, London (2022), and Moonlighting at studio1.1, London (2018).

Your paintings often deal with the unreliability of memory. Do you see painting as a way to recover lost memories, or to invent new versions of them?

There’s a great documentary about two Australian brothers, Tas and Ben Pappas, who rose up to become the top 2 skateboarders in the world in the late 1990s. The films title ‘All This Mayhem’ comes from a description by Tas of their childhood and turbulent home life being surround by all this mayhem. In the film when discussing his ongoing feud with Tony Hawk he says something like ‘There are three sides to every story, your version, my version and the truth’. I think about this a lot and the idea feeds into the paintings, what I paint is my take on things that have happened in my life. I like that painting physical images can and does create or update the memories or images in my head of certain life events, particularly traumatic ones, and that they can also mark their significance. I also like that it can help me to loosen those memories, it’s a kind of way to work through them and move on.

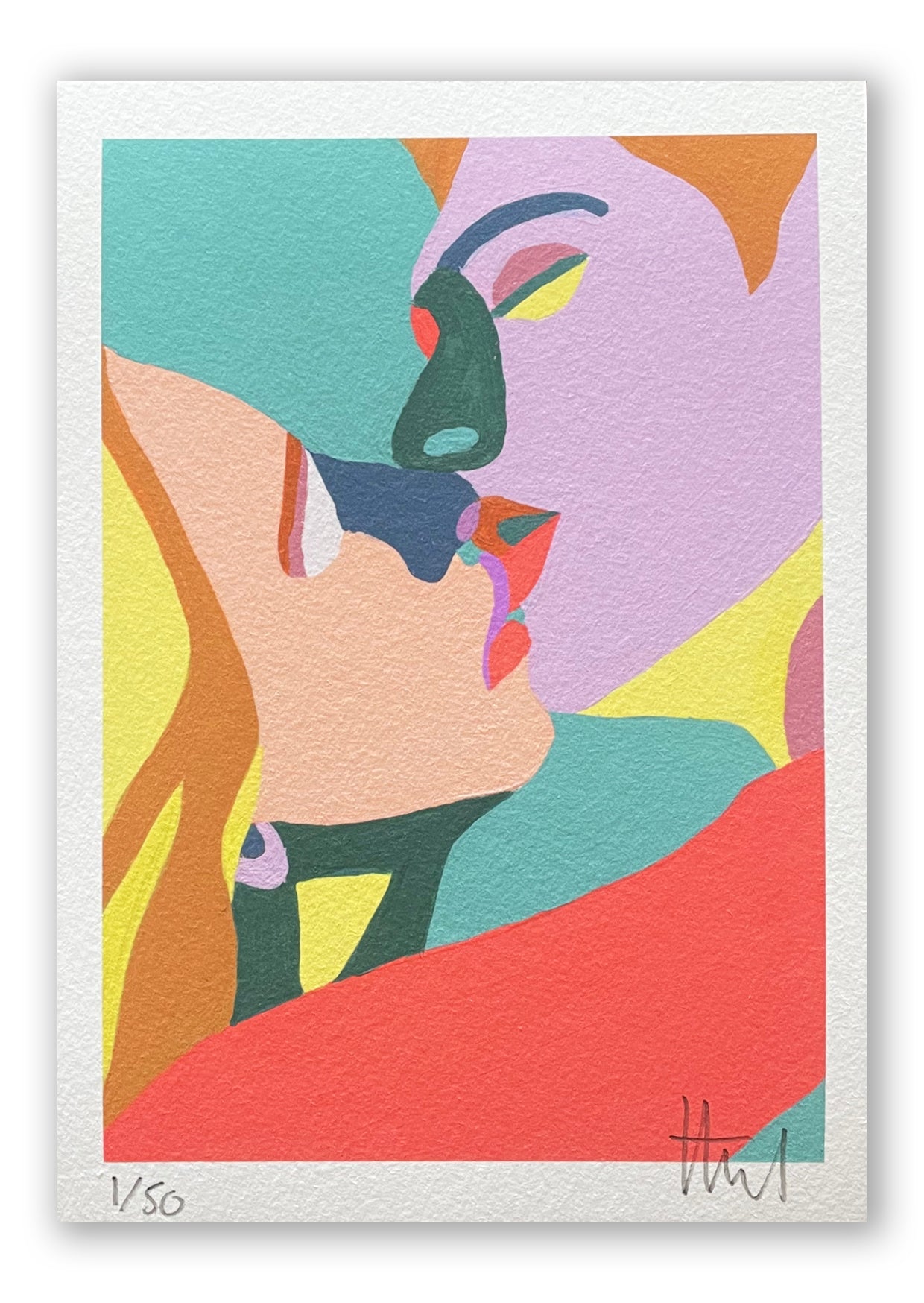

Lot 57. Marcus Cope - All We Need

Many of your works seem to turn painful and personal memories into something mythic. What role does symbolism play in your understanding of grief and transformation?

The symbolism in the works is personal, and I always wonder how much of the story of each work I should share with the viewer. It’s interesting for me to think of the role it plays in my understanding of transformation, which I think it does. For example, A few years ago many of the paintings had a horse in them, and that horse was representative of my grandmother. After a while, I decided I couldn’t keep putting horses in pictures, and with that realisation was also the realisation that I had got beyond thinking about her. I like symbolism because it allows me to say something, or suggest it deeply, without being too descriptive. For example I’ll often add a wine bottle, or beer can into an image. For some, that’s just detritus, or still life, but for me it’s representative of much more. My father was an alcoholic (so it brings a whole childhood of memories), and I’ve felt that struggle myself with alcohol. So it’s significant, particularly for me to keep going forward and developing as a person, and as a parent. My life is there in my pictures.

You’ve described rewriting your story through painting and parenthood. Do you feel that your work now carries a different kind of inheritance, one of repair?

I’m often asked this, if painting is somehow cathartic for me? When I was seeing a therapist she said a similar thing, that I seemed to use painting to work through past trauma and difficulties, to find a path through those towards light and hope. I think it can and does do this to a degree, but it is also about the process, giving over my mind to the painting and it becoming a totally immersive endeavour. Each good painting has those periods in the studio, usually the last few days of work on it where it takes me out of myself, and I guess in a way that’s what I’m doing it for.

Some of your work has been inspired by time spent abroad, how has place shaped your visual language?

Many of the paintings make reference to places in Cyprus where I have spent a lot time since first going there in 2003 on an artist residency. People familiar with the country used to say to me that they could feel Cyprus in the images, and although that was never really my intention, it lead me to wonder about the visual connections I enjoy there with what I enjoy looking at in painting, and subsequently the light and surface I end up settling on when completing a work - I think this is a dryness of the surface and a slightly bleached out palette. The specifics of a place in each work is very important to me, aside from Cyprus they are generally my childhood bedroom, places in Trowbridge town (where I grew up) and my local neighbourhood in South London. I think about these places and either I use photos I have taken as reference (or I take pictures), or I make up the scene using memory, or else sometime I use google street view for somewhere specific.

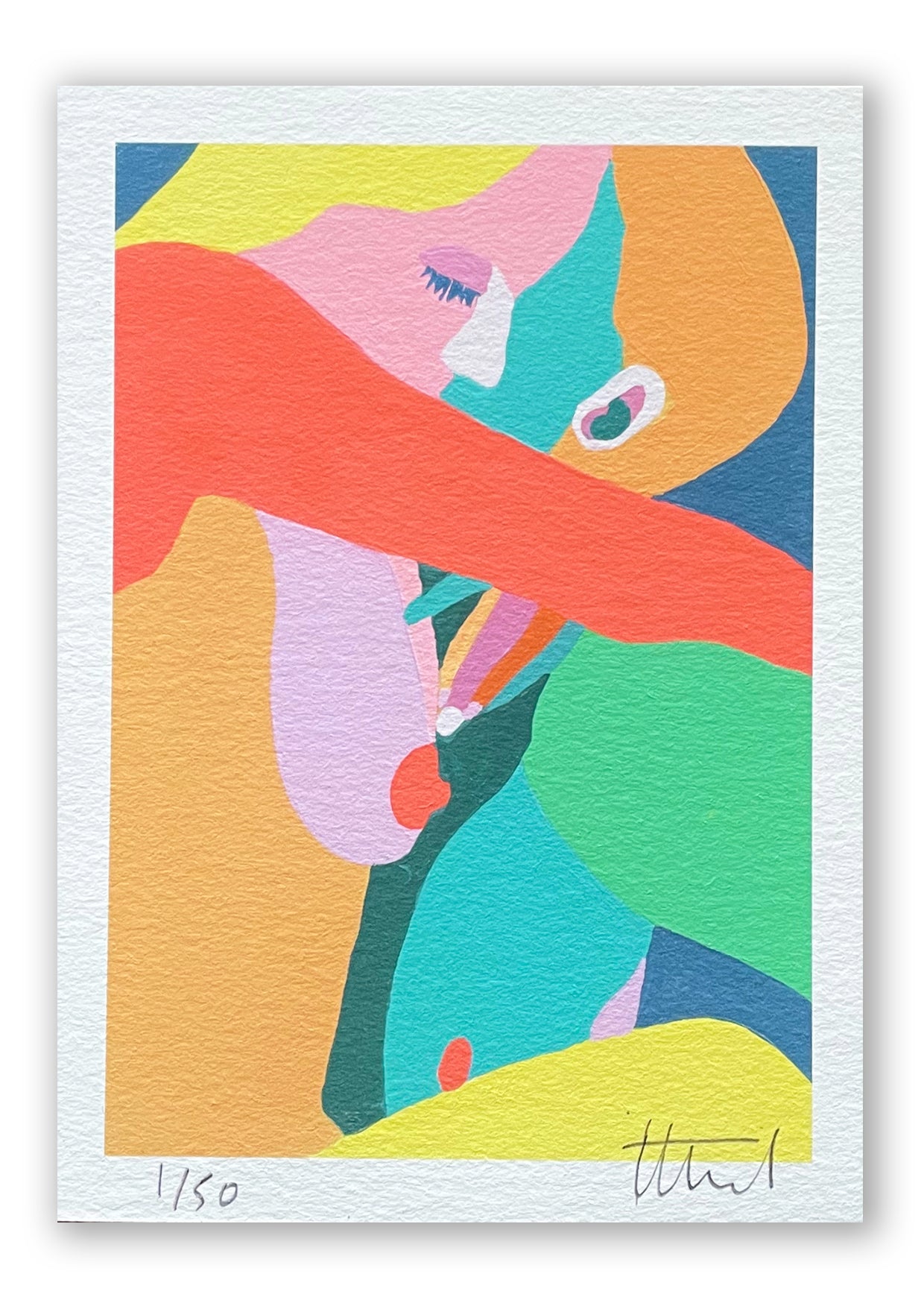

Marcus Cope, Surrender, 2025, oil on canvas, 180 x 260cm, BJDeakin Photography.

The colour palette in your paintings can shift between dreamlike and dissonant. How intuitive are your colour choices?

Dissonant means unharmonious, right? I kind of like that. I don’t really like the colour blue, so I’m always much more careful with that than all other colours, I also am very aware of the white in paintings. On the whole, along with surface and mark making, it is all intuitive, but I will also say that I think what comes with that is a kind of dumbness. I never know how to paint something, so I’ll try and try and try again, and eventually I get something that just works - for me - and I can leave it. Colour is all wound up with composition. If a painting isn’t working, I might decide to start removing colours, paint out all the yellows or oranges etc, to create what seems, to me at least, to be harmony. Alternatively I’ll sometimes give it a wash of a translucent colour, to bring it all together. What this also does is alter all the colour choices I have previously made on the work, so it can transform a painting quite quickly - an orange wash will warm up a painting, a yellow one will turn the blues green and the reds orange, a black one will create a depth, etc.

The theme for this year’s Sound and Vision centres on the lyric “If I only could, I’d make a deal with God.” Were you directly influenced by the lyric, or did you approach it from a more personal or alternative perspective?

I’m not sure you can get much more personal than making a deal with god - although as the lyric suggests I’m pretty sure God is not a deal maker. It’s not a literal translation, I can’t work that way these days.

Thinking of All We Need, 2025, can you talk us through some of the elements in the work? The cloud that appears to swallow the figures’ heads, and the ancient stone head?

The scene is one I’ve painted several times, Molos, a promenade in Limassol, Cyprus. For a long time it’s been a ‘go to’ place, in my mind. I often find myself daydreaming and wandering around there. I have many memories of spending time there, calm. I follow a couple of instagram accounts who post images daily of the area. It’s a draw for me mentally. When I was last there in Cyprus I did a drawing of the two people, with their heads in the clouds, and masks floating in front of the cloud - as in the painting. I was thinking about desire, how I used to want to live there in Limassol, and for a while I did. And how desire changes, particularly as we get older and we understand more about the world and the limitations that we face. So I was taking a childlike approach to the picture, to make a deal with god is a fantasy, like when you are a kid and you dream about winning the lottery or living in a mansion - as you get older you think more outside of yourself, and realise health, caring or living within our collective ecological means might be better options, for everyone, to have all we need, rather than all we want. Yoko Ono had a wishing tree at her recent Tate show, my daughter wrote two wishes either side of a piece of paper to hang from the tree, to become a gymnastic pop-star on one side, on the other, world peace! I was so proud of her.

Do you have any projects on the horizon that you would like to share?

I’m just in the studio daily, giving myself a hard time, trying to make the best paintings I can and not settle or be lazy. I just had a solo show at the Bomb Factory in London, from which two of the works sold to the Pinault Collection.

Visit Marcus' Website.

Questions by Victoria Lucas.